Dani Benavides is a sophomore at NAI. This is her first year writing for NAEye, and she moved to Pittsburgh a year ago from Utah. She likes watching basketball,...

Part of an ongoing series exploring issues of identity for students at NAI. Disclaimer: All of the stories in this series are personal experiences from first-generation immigrants and are written to express how the author perceives their situation.

February 6, 2020

Picture this. You’ve just moved from Utah, a state with a Latinx population of 14%, to Pennsylvania, a state with half the number; specifically 1.5% in Allegheny County.

You’re in Giant Eagle paying for your groceries when the bagger hears you and your mom speaking Spanish. He gives you a look with such disgust that you feel your stomach drop and your cheeks turn red. He then begins aggressively and carelessly chucking your groceries into bags, still giving you and your mom constant glares.

But get this: this isn’t the first time something like this has happened.

Last year after class, one of my friends thought it was really cool that I speak Spanish and wanted her friend to hear me say something. We walked up to him, and she turned to me and said, “Say something! Say something!” So, I said something random in Spanish. Her friend looked me dead in the eye and said, “Go back over the border.” They both laughed, turned around, and walked away. I was shocked. I didn’t know what to say or do, or anything. To this day, I still regret not calling him out for what he said.

Later in the year, Moe’s Southwest Grill (a Mexican restaurant) came to the school to provide food for Cinco de Mayo. Waiting for my friend to get more food, I walked over to talk to some other people sitting at a table. One of the boys there saw me approach them and snarkily said, “Is this authentic enough for you? Are you enjoying your culture?” The entire table, including my “friends”, laughed. I was so embarrassed and couldn’t find any words to say, so I just walked away.

Even to this day, when I find myself in these situations, I just freeze and am at a loss for words at the moment. I later think about what happened and go over all of the things I could’ve but didn’t say and get mad at myself. The stories could go on, but I didn’t really need to find words to say before; I only recently started experiencing racism this harshly.

When I lived in Utah, ignorant remarks wouldn’t be as blatant; people would just make dumb jokes. Usual things I’d hear would be generalizing all Hispanics as Mexicans or people assuming I’m Mexican (and I’m not; there are 20 other Spanish speaking countries), being asked if I “speak Mexican”, and getting judgmental remarks about the food I’d bring to lunch. I even knew a girl who would mock and ridicule me every time she heard me talking to my family or friends in Spanish, saying things like “Taco sombrero burrito”.

Since there are so many more Hispanics in Utah and at the school I went to, considering the geodemographics, people were more accustomed to the kind of diversity there; so these things wouldn’t really happen. This was something that shocked me when I moved here. Hispanics are so much more foreign to people here, and I wasn’t used to feeling so out of place. Because of this, I feel it’s more important than ever for me to stay in touch with my roots and be proud of where I come from.

But what disturbs me the most is that I know if I was brown, I would have a lot more of these stories to tell. Usually, people don’t know that I’m Latina until they hear me speak with my family, hear my parents’ accents, or learn my name; but I can’t even imagine how much worse things are for Brown Latinxs. If I wasn’t white-passing, all of those experiences could’ve potentially happened before people heard me or got to know me. I would just be immediately “spotted”. I think it’s important to acknowledge this, as colorism is very prominent and active in our society. So even with these bad experiences I’ve had, I know that some other people have it much worse.

Once, my mom and I were having a discussion with a previous music instructor I had. He asked us if there were CDs in Colombia. Even if that sounds unbelievable, this is how many people think. Our countries can be thought of as extremely underdeveloped, and those stereotypes imprint onto the people.

As frustrating as it is to constantly hear ignorant remarks from people, it feels as if I’ve gotten “used to it”. I recall a time later in my freshman year when a kid at my lunch table told me to “get deported”; I didn’t care nearly as much as I would have before. I’d gotten so used to people saying things of the same matter and I know that if it would have happened any earlier, I would’ve been extremely upset about it. But it didn’t affect me as much anymore, and that shows a much deeper problem than a simple lack of concern. Rather, it reflects our society’s forced desensitization as a whole.

I’ve never felt as if I had to be more American; it’s always been the opposite for me. Because of all these things I’ve experienced and what other people like me are experiencing, it’s always been instinctive that I should be proud of who I am, embrace it, and express it. But even while knowing this, I still feel hesitant. At times I feel that people get irritated if I bring up my roots multiple times and I worry that I’m “rubbing it in their faces.”

Ever since moving here, I still get scared out in public that someone will overhear my family and me talking and make rude remarks. When my dad announced that we were moving to San Francisco at the end of Sophomore year, the first thought that came into mind was that there would be more people like me. San Francisco’s Latinx population is 15%, 39% in California overall. Being that this was the first thing I thought of, it’s sad because I shouldn’t have to be grouped together with people of the same cultural background to feel comfortable with myself.

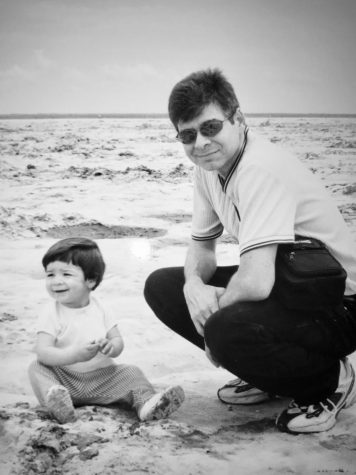

My parents always taught me to stay true to myself. They continuously remind me about how Latinxs face just as much oppression as other minorities, even though it seems as if nobody really talks about it. My dad immigrated to the US in 1994 from Costa Rica and my mom around the same time from Colombia. They constantly emphasize how lucky I am to be living here, and that their immigration gave me opportunities I would’ve never received if still living in Latin America.

Yes, I will always be called “la Gringa” by my family, being the only American born out of all of us. Yes, some Hispanics who were born and raised in their countries probably think of me as “whiter” than them. Yes, I go by Dani because I don’t like the sound of my full name (Daniela) in English. Yes, people may sometimes still talk to my mom slowly and loudly thinking it’s necessary because of her accent. And yes, it’s guaranteed that I will sometimes feel out of place with my other American friends, but that’s just what’s bound to happen when a mix of backgrounds is introduced.

Despite all of its disadvantages, however, I am, like how my parents always say, still grateful to be living in this country.

Honestly, I don’t really know if I’ve found a balance between my two cultures and that’s okay. Cultural identity is a confusing concept to attempt to grapple. But in the end, I know that no matter what, I’ll always stay true to who I am.

Dani Benavides is a sophomore at NAI. This is her first year writing for NAEye, and she moved to Pittsburgh a year ago from Utah. She likes watching basketball,...

Beth Sondel • Mar 5, 2020 at 1:09 pm

Wow, Dani. You are talented beyond belief! This is such powerful writing and an incredibly important story to share. I’m so sorry to know that you have to put up with all of this, but not surprised at all that you have found ways to stay strong, to have pride in who you are, and to use your voice to advocate for systemic change!

Martha Lucía Mesa • Feb 12, 2020 at 4:19 am

Excelente artículo Daniela, que orgullo para todos en Latinoamérica poder leerlo. Gracias por ese hermoso reconocimiento a tus raíces y en especial felicito a tus padres por haberte criado consciente de donde vienes y quien eres.

Thank you Dany, wonderful, congratulations you are very smart girl and excellent human been.

Allen M • Feb 11, 2020 at 11:16 pm

Incredibly powerful article, I didn’t even realize it was you writing it until after I had finished. You’re an incredibly talented writer; it takes a lot of courage to talk about this kind of stuff. Proud of you!

Vanessa • Feb 11, 2020 at 9:43 pm

Estamos muy orgullosos de ti querida Dani! Dios te bendijo trayendo esta tremenda reflexión que, estoy segura, identifica a muchos…

Sigue así hijita querida, me encanta que tengas esa sensacion de confusión sobre tus 2 culturas, sabes? Era una persona del mundo!!! Nunca lo olvides! Estas en un nivel y experiencia social y cultural que pocos han experimentado!

Un abrazo enorme! Felicitaciones!!

Maria F • Feb 11, 2020 at 8:02 pm

Excelente artículo, Dani. Muchos jóvenes, como mis hijos, probablemente se identifican con todo lo que has escrito. Sigue adelante!!

Maritza Arce Larreta • Feb 11, 2020 at 5:26 pm

Excellent article Dani! What is most important is that you are proud of your heritage, Colombia as example is a great country with an old civilization and deep history, the same is for Costa Rica. I will never forget a classmate in nursing school asked me if we have refrigerators in Peru. I responded that I was surprised of her ignorance and that she needed to read and learn more. You speak two languages, you have a wonderful family, you have been in other countries, educate those ignorants and feel sorry for them. Be proud of being Hispanic!!!!!

Love your article!!!!

Nora Boydstun • Feb 10, 2020 at 10:39 pm

Love it ! You are an amazing writter ….keep writing. Love you so much ❤️❤️ Gringa !!!Te amo !!

Alba • Feb 10, 2020 at 9:47 pm

Great article!

Donna R Etchart • Feb 10, 2020 at 7:37 pm

Dani, we miss you and love you here in Utah! What a wonderful article and a unique perspective! Your writing is eloquent and powerful. Keep it up!

Liliana Davies • Feb 10, 2020 at 6:51 pm

Excelente Dani totally awesome

Angela Castano • Feb 7, 2020 at 3:59 pm

Love it!…especially our pic

Claudia • Feb 6, 2020 at 9:36 pm

We are very proud of you!!

Michelle • Feb 6, 2020 at 6:11 pm

Absolutely fantastic.

Sally • Feb 6, 2020 at 5:23 pm

Amazing article, Dani!