COVID-19: One More in a History of Xenophobia

COVID-19 was not “the China virus” a year ago. It still isn’t today.

The xenophobia faced by the Asian American community because of COVID-19 is unjust.

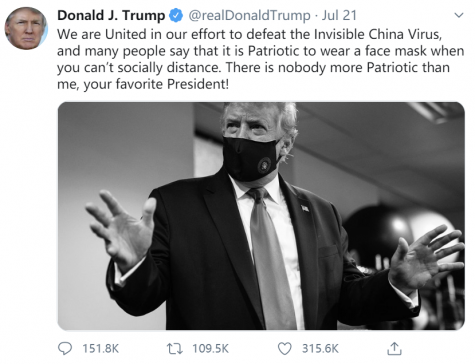

In March 2020, Donald Trump sent a tweet referring to the coronavirus as “the Chinese virus”, drawing shock and anger from many. Officials such as the head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have criticized the act for promoting racist associations between the virus and those of Chinese descent. However, the act of attributing diseases to marginalized groups is not new, and it is in fact rooted in a history of xenophobia.

The 14th century, for example, saw the persecution of Jews during the bubonic plague. Jews had already become a minority in medieval, Christian-dominated Europe by that time, and lack of tolerance for unfamiliar customs led to increased tensions between the two groups. When the Black Death arrived, Jews were found to be an easy scapegoat, and they were blamed for spreading the infection or poisoning wells. Over 200 Jewish communities were wiped out between 1348 to 1351 as a result.

As a more recent example, as WWI ravaged on in 1918, flu season took hold. At first, it seemed like any other flu – a particularly contagious strain, yes, but no more lethal than any others. Then a second wave hit. First observed in Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia, it soon spread around the world, infecting an estimated 500 million people and killing about 50 million more. It later became known as the 1918 influenza, caused by an H1N1 virus with avian origins.

It is sometimes referred to as “the Spanish flu” as a result of many falsely attributing this deadly disease and its origins to Spain. However, this is inaccurate. In actuality, Spain was one of the only countries actively reporting its cases. Whereas other countries such as the United States suppressed coverage of the flu during wartime censorship, Spain, as a neutral country, was able to report their cases freely.

Unfortunately, this meant that much of the world believed the pandemic to have started in Spain, leading to stigmatization. For example, one popular poster portrayed the disease as a woman known as “The Spanish Lady”, the implication being that she was a prostitute who hailed from Spain and was spreading the infection throughout the world.

Put simply, despite honestly reporting cases, Spain and minority groups associated with the country were unfairly associated with one of the most deadly pandemics in history, resulting in undeserved biases.

In 2003, a serious new type of pneumonia started spreading from Asia. This virus was later coined the term “severe acute respiratory syndrome”, or SARS, by officials at WHO (World Health Organization). However, not many are aware that this name was decided specifically to prevent the disease from being named the “Chinese flu” or something similar.

Naming a virus after a region or group of people has had negative impacts by stigmatizing certain communities in the past. For example, when MERS, a distant cousin of SARS, was first discovered in Saudi Arabia in 2012, researchers agreed not to name it after the place where it was first reported. Instead, they named this new virus MERS, or “Middle East respiratory syndrome”, as it referred to a much broader region and did not single out a single country. However, even though the region was broadened, there were still “unintended negative impacts by stigmatizing certain communities,” according to Dr. Keiji Fukuda, Assistant Director-General for Health Security, WHO.

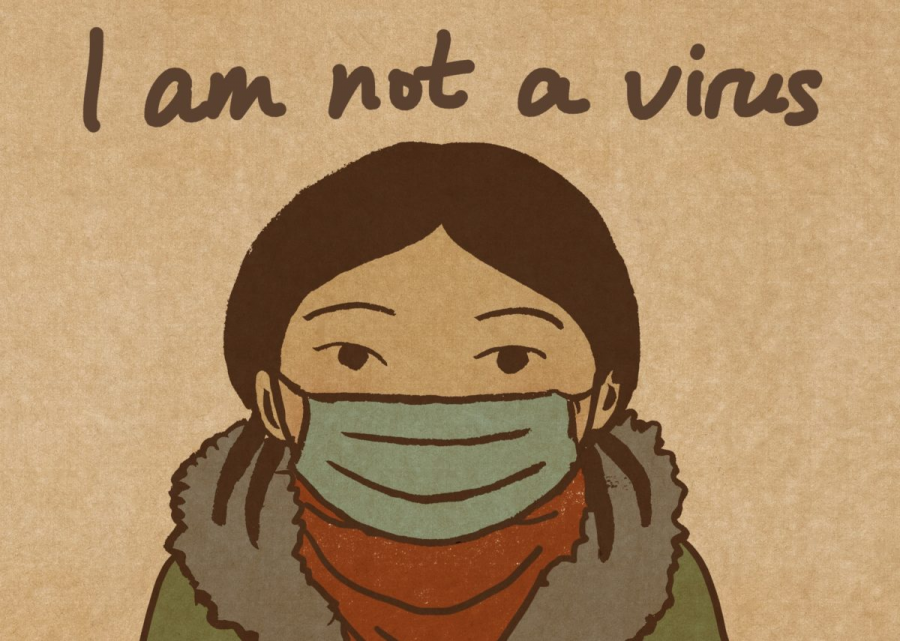

So, what does this mean for calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus”? By labelling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus”, it represents the virus as invasively foreign and often places the blame of the spread of the disease on an ethnically defined “other”. There have also been hate crimes against Asian Americans after COVID-19 began to spread to the United States. Numerous accounts of Asian American adults and children being assaulted, verbally abused, and bullied have been reported. In fact, in a recent Pew Research Center study, 4 in 10 Americans say it has become more common for people to express racist views against Asians since the pandemic began.

Overall, associating diseases with certain ethnic groups or regions have led to stigma in the past and present. Marginalized groups have often been the most negatively affected by pandemics and there is a persistent belief that if you are not part of the group, you are less at risk. Throughout history, naming a particular disease after a region or group have only had negative consequences such as discrimination and racism. Today, linking COVID-19 to those with “Asian appearances” is incorrect and will only encourage stigma. Furthermore, calling the disease the “Chinese virus” is a misnomer, as pandemics see no national borders.

Recently, the World Health Organization has even created new guidelines for naming new human infectious diseases. In these guidelines, WHO says: “cities, countries, regions, continents” should be avoided in disease names.” Accordingly, calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus”,“Kung flu”, or “China virus” is not acceptable in the first place.

As Dr. Keiji Fukuda says, “This may seem like a trivial issue to some, but disease names really do matter to the people who are directly affected. We’ve seen certain disease names provoke a backlash against members of particular religious or ethnic communities, create unjustified barriers to travel, commerce and trade, and trigger needless slaughtering of food animals. This can have serious consequences for peoples’ lives and livelihoods.”

Words are powerful. Let’s make good use of them.

Ada Sun is a sophomore at NAI, and this is her first year writing for the NAEye Newspaper. She enjoys relaxing and eating ice cream.

Maggie Mu is a sophomore at NAI. This is her first year writing for the NAEye Newspaper. She has a love of puns, and in her free time, she enjoys reading,...

Bill • Mar 21, 2021 at 9:16 pm

You hid behind the internet to blame the authors. You are really a racist and brainwashed coward. What’s your real name?

COVID-19 was an ‘OUTBREAK’ in China. It did not originate in China. There is not enough scientific evidence to support your “comes from China” nonsense.

This study, which was published in the Tumori Journal, sheds light on the possibility that the virus had been spreading in Italy well before the outbreak was reported in Wuhan, China: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0300891620974755

Maggie Mu • Mar 13, 2021 at 11:55 am

Matt, that is not the issue with calling the COVID-19 virus “the Chinese virus.” According to the Oxford Dictionary, “Chinese” means “relating to China or its language, culture, or people.” When someone calls the virus “Chinese”, they are not “calling something by what it is.” They are, however unintentionally, associating a worldwide pandemic with an entire group of people and their culture, as though the two have anything to do with one another. As a hypothetical example, imagine if someone called a particularly virulent illness “the American disease.” The implication is that the country and its people are to blame for the sickness. That is not okay.

I am not a virus. My people aren’t a virus. We should not be associated with a virus when there is the perfectly serviceable name of “the COVID-19 virus”, a name chosen by the WHO to avoid this exact issue.

Matt • Feb 25, 2021 at 10:59 am

But it comes from china. With the Spanish flu and black plague they didn’t come from Spain and Jews. I think your the real racist for reading into someone calling something by what it is