The Art of Practice

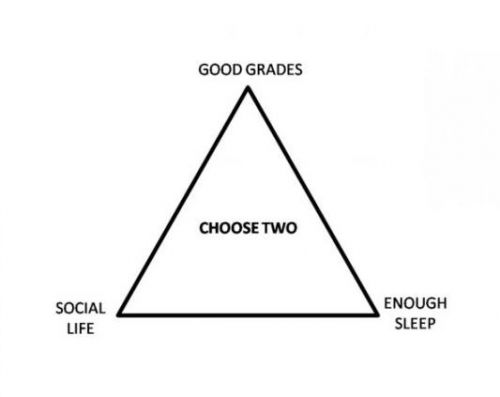

Choose two of the following: enough sleep, good grades, or a social life. This is the dilemma of many high schoolers. But what if you didn’t have to choose? Is it scientifically possible to have all of the above?

Many students choose “good grades” as one of their options. To achieve good grades, the average student spends about 17 hours per week studying. But time isn’t infinite, and in order to make time in their schedules, students often neglect either their sleep or their social lives. With this information, we can piece together an answer to our question: decrease the amount of time studying, so that your time can be spent doing either of the other two options.

the average student spends about 17 hours per week studying

That gives us our first criteria for an answer – the optimal study session should be short, in order to accommodate for busy schedules. However, shortened sessions should not clash with results, since students still want good grades. Therefore, our second criteria is retention. Students should be able to retain the information that they studied for. In order to understand how humans retain information, we need a basic understanding of the human brain.

The human brain consists of billions of neurons, which are small nerve cells.  These neurons store information by making connections with other neurons, forming a highway of information. Retention, in terms of the brain, is the strength of these connections. Everytime certain information is used, the connections that store it become stronger (keep in mind this is an oversimplification of the subject). With all of this in mind, we can begin to search for the best way to study.

These neurons store information by making connections with other neurons, forming a highway of information. Retention, in terms of the brain, is the strength of these connections. Everytime certain information is used, the connections that store it become stronger (keep in mind this is an oversimplification of the subject). With all of this in mind, we can begin to search for the best way to study.

The most common studying method, the one that you probably use, is referred to as “blocking.” This means thoroughly studying one subject at a time before moving on to the next. If an imaginary student, Bill, has to study for chemistry, math, and english, blocking means that he studies chemistry thoroughly, then moves on to math, and so on.

However, blocking fails to meet our second criteria – retention. To explain why, let’s return to Bill. When Bill is studying for chemistry, his brain begins to form new connections between neurons, storing this information. The common misconception here is that this information is secure in his long-term memory. But it’s not. Bill doesn’t use this information on a regular basis, so this information is only stored in his short-term memory. As soon as Bill moves on to study for math, his brain clears his short-term memory to make space for the new information. That’s why students who practice blocking can often only remember the fundamental information, which is practiced often, rather than the specifics, which are rarely used.

What does this mean? All of Bill’s hard work was essentially put to waste, since his brain never needed to use that information until a later point in time. When Bill studied for math, his brain wiped the chemistry from his memory. When he studied for english, his brain wiped the math. This is why students practice blocking often retain the last subject they studied the best – since there is no new information for the brain to store, the last subject is kept safe in their short-term memory.

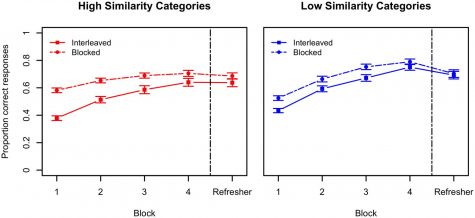

Scientists have observed this phenomenon and began to endorse a second studying method: interleaving. This is when students mix, or interleave, the subjects they have to study for. Instead of studying for chemistry and never returning to it, Bill would study a little bit of chemistry, move on to math, then return back to chemistry. This has a vastly different effect on Bill’s brain than blocking does. The first time Bill studies chemistry, his brain wipes his short-term memory. But when he returns to it, his brain is forced to retain that information in his long-term memory.

students who practice interleaving can boost their scores by 25 percent

This passes our second criteria, retention, by flying colors. Studies prove this as well. When studying for a test the next day, students who practice interleaving can boost their scores by 25 percent. And if that sounds good, interleaving when studying for a test a month later (such as midterms or finals), can boost scores by an astonishing 76 percent. But does interleaving pass our time constraint? Does it use shorter sessions? The answer to that is a little trickier.

If Bill switches to interleaving, the results will not be immediate. The first time he studies chemistry, then moves on to math, his brain will still wipe his short-term memory. This often means that students who interleave are forced to study extra when they first start. However, every subsequent time, the connections will only get stronger.

Bill’s new study schedule would look something like this: chemistry, math, and english. He practices briefly, only spending about 15 minutes on each topic. But when he finishes the set of all three, he returns back to the beginning, repeating the process all over again. By the time Bill is done, he’ll get all the practice he needs while retaining the information better than ever before.

But nothing is perfect, and this holds true for interleaving as well. Oftentimes, taking the first step is often the hardest decision to make. Students who practice interleaving often report frustration and anger when they are forced to study extra for the first few times. They tend to give up on it and assume that blocking is better. But if they weather the storm, science has proven that interleaving can be a significant boost to their education. Keeping all of this in mind will set proper expectations and prepare you for success.