Women hidden in History: Ada Lovelace

Portrait of Ada Lovelace, a pioneer in computer science and engineering.

March 31, 2022

Ada Lovelace was born Augusta Ada Byron in London, England, December 10, 1815 to Lord Byron, a famous poet, and Annabella Milbanke Byron, who divorced 2 months after her birth. Her mother was known to be highly intellectual and enthusiastic about mathematics and science while her father was seen as unstable and unpredictable. He passed away when Ada was 8, so she never got to know him personally.

Ada’s mother seemed to have no emotional attachment to her, so her maternal grandmother and the house servants raised her. Ada’s grandmother passed away when she was 7 and Ada herself suffered from poor health well into adulthood.

At the time of Ada’s childhood, there were no schools for females in the UK, but because of her family’s wealth Ada was able to have a private tutor. One thing Lady Byron was very serious about was her daughter’s education. She wanted her to focus on mathematics and science in hopes that she wouldn’t become like her father. She hoped that with enough education and punishment her daughter would become highly disciplined and serious unlike her father’s wild spirit.

Lady Byron saw to it that Ada had education in French and music since music abilities, the ability to read, and the ability to properly make conversation was becoming more socially acceptable for women.

Ada’s mother was very strict with her, demanding that she work very hard and when Lady Byron felt she did less than expected, Ada was put into isolation, sometimes for days.

Ada’s entire life changed when she was 17 years old. Charles Babbage, a Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, invited Ada and her mother to come see a small-scale version of the calculating machine he was working on after hearing of their knowledge in Mathematics.

Ada was captivated by his concept but felt there was little she could do for him. She requested his blueprints to help better understand how the machine worked. Ada and her mother often went to see steam driven machines in action to learn how they worked, one being the Jacquard room which was controlled by punch cards or machine code.

Ada continued her search for mathematical knowledge and became friends with Mary Somerville, one of the first female mathematicians of her time. They discussed modern mathematics, challenged each other to think on a higher level and even discussed Babbage’s machine.

At age 19 Ada married William King and had 3 kids with him between 1829 and 1836. She began working on advancing in mathematics with the help of Mary Somerville and Professor Augustus De Morgan of University College London.

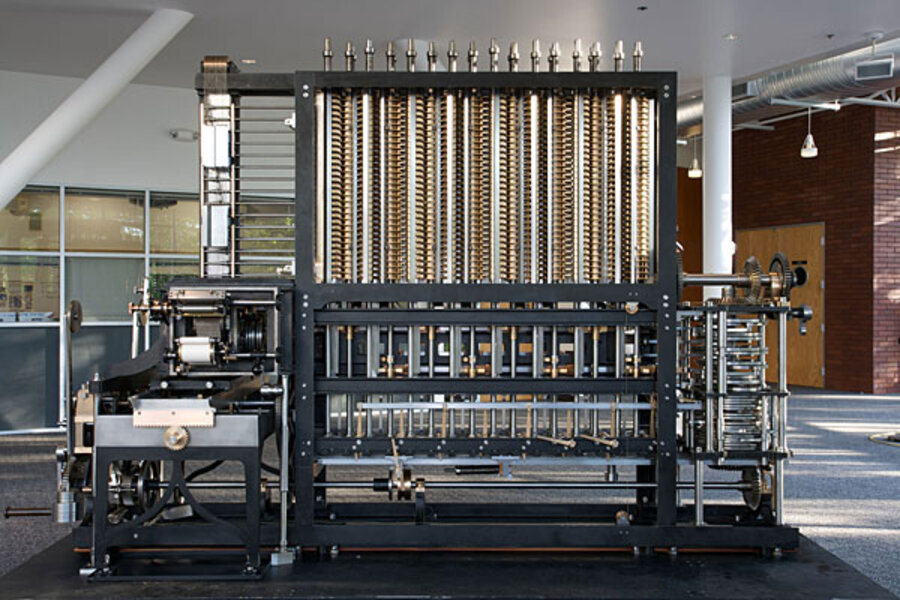

In 1842 Lovelace caught wind of a paper written by Luigi Manabrea, an extremely successful engineer, about Babbage’s new invention the analytical engine and the paper itself was written in french. The analytical engine was way ahead of its time. It was capable of more sophisticated calculations and was the world’s first programmable computer.

When Ada finally got ahold of the paper, she translated it and gave it to Babbage. When asked why she didn’t just write a better version herself, Lovelace responded by adding notes that were 3 times more in depth than the original work.

She provided notes on how the engine calculations work, corrected Babbage’s miscalculation in the Bernoulli Numbers, one of the most difficult calculations to complete, and included the world’s first computer algorithm, the Bernoulli Number Algorithm. Some people argue that she shouldn’t be credited because of the work Babbage did, which makes this a debatable topic among some mathematicians.

Ada realized that the engine could go beyond numbers, it could be designed to process all sorts of things, for example, music. She realized that as long as it could be translated into numbers, things like music, images, and even the alphabet could then be processed by the algorithm and manipulated into code.

Sadly, after her translation Ada got sick and died at age 36 from what was speculated to be some form of cancer. Babbage ran into financial problems and was never able to build the computer model he had hoped to, but in 1991, Doron Swade a computer curator at London’s Science Museum was able to build it. The computer weighed 5 tons, but after 2 minor fixes, it worked perfectly.

Lovelace is known in the engineering and computer science community but the majority of people have little to no idea who she is. History textbooks include the same small group of women over and over again, women like Rosa Parks and Amelia Earhart, but there are more women like Ada Lovelace that also deserve their time in the limelight for the contributions they made to a society that wanted to suppress them.